SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 2014

There was much good cheer and buzzing conversation as members of our group arrived, so it took some effort to move everybody into the living room to begin our discussion.

But we managed! At about 8:35 pm, with our glasses refilled with wine and the fire roaring, we began meeting #2.

1. An Overview of Epicureanism

Before we began in earnest, I thought it might be helpful (particularly for those who had not had a chance to look at the readings), if I briefly summarized the philosophy of Epicurus.

I mentioned that, along with some other thinkers of his time in 4th century BCE Greece, Epicurus believed that everything in the universe is made up of tiny, indivisible particles — which they called “atoms” (a term that would be co-opted by chemists and physicists in the 1800s, so as to become familiar to us today).

From this Epicurus concluded that our universe is entirely material.

Despite his materialistic understanding of nature and the larger universe, however, Epicurus was not a determinist. He accounted for free will by way of something he called the “swerve,” in which one atom unpredictably changes its course. (At least in a poetic sense, this notion of a “swerve” brings to mind the discovery in quantum mechanics of wave-particle duality, i.e. whether a photon expresses itself as a wave or a particle will change, depending on what we do to it. Though, we might note, the question of free will is no closer to being clarified today than it was in ancient Greece!)

But enough of these speculations about the physical world… What did Epicurus have to say about how we should live our lives?

Epicurus argued for a simple, streamlined life, with a focus on friendship and reflection.

His famous four rules are:

i. Gods, if they exist, are not relevant to human life. He acknowledged that gods may exist, but he dismissed any possibility that they might be willing to intervene, or even show concern for our needs, in any way.

ii. There is no afterlife. When we die, that’s it… Sorry if you had your hopes up for mingling with Achilles and Patroclus in the Elysian Fields!

iii. Pleasure is available to us with minimal effort. He maintained that almost all of us have enough resources available to us, already, to secure our pleasure — a little water, a little barley, and you’re good! The rest of it is a distraction, not necessarily to be shunned (that extra piece of caramel is fine, take it!) but best if understood as such.

iv. Pain is not worth getting worked up about. As for suffering, Epicurus reassured his followers and readers that it is very rarely chronic and intense at the same time — so it shouldn’t cause us too much anxiety.

This notably human-centered, pleasure-seeking, materialistic philosophy was almost lost, following the conversion of the Roman Emperor Constantine to Christianity in 313 CE and the triumph of the monotheistic traditions during the Dark Ages.

Except that it wasn’t lost entirely. It happened to get smuggled into the Renaissance — in a beautiful form! In the year 1417, a well-to-do adventurer and budding humanist, Poggio Bracciolini, set out from Italy to look for old Latin manuscripts. Poking around the library of a remote German monastery, he came upon a manuscript called “On the Nature of Things” by the Roman poet Lucretius, who had lived in the first century BCE.

By bringing Lucretius’ poem back to his circle of friends in Florence, Poggio preserved for us a faithful rendering of Epicurean thought, and one infused with great feeling. Copies of “On the Nature of Things” were passed, hand to hand, person to person, country to country, until Lucretius, and through him Epicurus, influenced such thinkers as Montaigne, Bacon, Shakespeare, Galileo…

Yet the story doesn’t end there, either.

For Stoics in the Roman era, and Christians and monotheists of all kinds ever since, the materialist philosophy of Epicurus posed a threat to their invisible orders (the “logos” or “universal reason” for the Stoics; “God,” “Allah,” “Spooky Electric,” or what have you for the religiously inclined). Hence, despite the discovery of Lucretius’ poem, the dominant discourses in our world have come down very hard on Epicurean philosophy for all these years, turning it into the caricature we know today.

As a result, it is associated in many people’s minds with a lavish meal, or with a dissolute life-style. For most of us the phrase “Eat, drink and be merry” comes to mind when we think of Epicureanism.

Escargot, swimming in garlic and butter. A rich creme brûlée…

The gout.

That kind of thing.

Yet many have managed to look past this caricature, too, and they have found themselves drawn to Epicurean thought.

Thomas Jefferson, who called himself an Epicurean, managed to slip the words “and the pursuit of happiness” into the Declaration of Independence. No small feat, that, with no small consequences for American culture. In recent times the ubiquitous contrarian Christopher Hitchens liked to describe himself as an Epicurean. In London, the School of Life, founded by Alain de Bouton, and The Idler, have even attempted to build institutions around the ideas and practice of Epicureanism.

So what do we think of this earliest recorded effort to develop a non-supernatural outlook on life? What did members of our group learn from reading Epicurus?

2. Does Epicureanism Lead to a Passive Life?

With the overview done, I wanted to launch the group into discussion. So to provoke a reaction, I mentioned one aspect of Epicureanism that particularly nagged at me over the past few weeks, namely the question of whether the tenets of Epicureanism lead to a passive life.

For if we are merely seeking pleasure… and the highest pleasures, according to Epicurus, are to be had in friendship and reflection… then, if given the resources, wouldn’t we all retire to our own version of his “Garden”? Wouldn’t we all just lounge around all day sipping water, eating barley, and engaging in idle chit-chat?

What about leadership? What about risk-taking? What about courage?

What about — I don’t know — ISIS? The Keystone XL pipeline? Do we care? Or does the larger world just fade away?

Luis spoke up to say that when he was doing the reading he too sensed that there was something lacking in the Epicurean outlook on life.

He pointed out that it seems to have, as its basis, a kind of narrow, individualist point of view. Epicurus wants each person to seek to rid himself or herself of anxiety and pursue pleasure. But this ignores that we are social by nature, and always intermingled and connected with others. We care deeply about our immediate families, our loved ones, our friends, our neighbors, our fellow-citizens, our world… even our biosphere. And these concerns will sometimes weigh against our private pursuit of pleasure. “For example,” Luis cried out (impressing us all with his sincerity — lucky Sara, Julia and Marina!), “I would sacrifice my own pleasure, willingly, for the good of my family!”

Renée countered that, on her reading of Epicurus, he was not suggesting that a person should act selfishly on all occasions. Rather, Renée understood him to be saying that, by simplifying and streamlining your life, you will free yourself to enjoy your choices more, whatever they may be (including taking care of your family).

On a given occasion you may want to take a risk (like singing in public) or sacrifice for a relationship (like working ungodly hours to pay your children’s school tuitions), but these actions will be available to you precisely because you aren’t confused about gods or afterlife. You will pursue your choices and your life while being clear-eyed about the costs and rewards of your actions.

Yes, you can eat that caramel, or you can give it to your daughter (as Luis surely would), because you know you don’t need it; either way, now you know that it is a choice.

Gerry compared Epicurus’ teaching to the concept of “flow” developed by the psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi. As Gerry explained it, if you are a skier at first moguls seem overwhelming but later they become part of the enjoyment. Losing your self-consciousness and getting directly into the act of living allows you to focus on the right challenges instead of getting caught up in useless anxieties.

3. The Finality of Death

Next, we got into a discussion about how our acceptance of the certainty of our death affects our the way we live our life. Is Epicurus right that when we recognize death as mere oblivion it… loses its sting?

Yann mentioned that he wakes up every morning with a sense of enchantment at the details of the world — the leaves, the sunlight streaming through them, the seemingly endless opportunities for pleasure. He thinks that his awareness of death increases this pleasure in that it encourages him to cherish each opportunity as it comes. For example, all summer he overcame his natural resistance to putting on a bathing suit and getting wet. because he knew that the pleasures he gained from swimming will not always be available to him.

Ken, too, suggested that knowing that our time on this planet is finite gives our lives more value. He mentioned a poem that made a strong impression on him — about a rare white orchid that blooms only once a year…

I objected to this line of reasoning, though. I explained that for the life of me, so to speak, I just can’t appreciate this notion that the certainty of our impending deaths gives our lives more meaning… that the flower which blooms only once a year is all the more exquisite for it, etc. etc.

To me, life is exquisite while it is lived for the obvious reason that I am experiencing it. Anything outside of this consciousness experience is, really by definition, the least interesting thing in the world to me. So death’s limitation of my experience does not enhance the quality of my experience in any way, it merely… limits it. How about a thousand white orchids blooming, every day? I have no problem with that picture.

I read the following line from Nabokov to the group:

“The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.”

This brief crack of light, I argued, is all we have. I understand that, and like Epicurus I don’t expect more. But I would be quite happy to see it extended into a vast sea of light. Immortality would be wonderful. I can’t imagine feeling otherwise.

Walden suggested that he was more bored when he was young for the very reason that he felt an abundance of time ahead of him. Now that he is older, and he feels more scarcity of time, he is never bored. He suggested that the approach of death has added greatly to his interest in life.

I responded that for me the dynamics are quite different. When I was young I too was more often bored, it’s true. Yet I don’t think this was because I felt an abundance of time: rather, I suspect it was because I didn’t know what to do with my time! As I have grown older I am happy to report that, like Walden, I am never bored, but that’s not at all because I sense the certainty of death approaching me. In fact, I resent death because I can now fill time better, giving more love, paying more attention to details, doing more thinking about the complexities of the world. Let it go on! Death impinges on the abundance of time I crave.

To me, then, death does not lose its sting in any case, whether we praise it as a motivation and a limiting device (as Yann, Ken and Wadlen do) or dismiss it as a mere state of oblivion (as Epicurus did). It is still… terrible, awful… a source of (what an apt phrase!) mortal terror.

Manon agreed with me on this, sharing that she fears it and does not welcome it on any terms.

4. More on Dealing With Death

This got us into a discussion about the toll of death on the living.

Epicurus urges his followers not to worry themselves with thoughts of death, since after all it will not trouble us at all when it comes (since we will be gone). But he seems to leave out the fact that, for those still living, the death of loved one is devastating. Devastating. Again, to Luis’ point, his philosophy seems geared to the perspective of each individual alone, but doesn’t consider our entanglements with others.

Dean cited findings that show that, on average, people’s baseline happiness bounces back after the death of a loved one within a matter of months (this phenomenon is sometimes referred to as “hedonic adaptation“). “So I’m with Epicurus,” Dean announced, “We shouldn’t worry about it.” (Dean admitted that he had dressed up as Epicurus for Halloween, and spent the evening in a toga ridiculing the flights of fancy of religious people… Hey kids, look, it’s Epicurus… Run! He doesn’t fear death!)

I pushed back on this. “Dean,” I said, “I think you are being a little cavalier, aren’t you? Yes, people’s self-reported “happiness” might bounce back, but that particular data stream is only a measure of one aspect of their experience. Even in cases where a person facing grief can find some equanimity, the death of a loved one will often reorient his or her outlook on life in a fundamental way, right? Sometimes for better, sometimes for worse. A wife may never regain her former ambitions after the death of her husband, or a father may find himself oddly drawn to stories of loss and heartbreak, seeking to help those in need. Or those who have lost someone close to them may begin to cherish their friends and family more than ever. These changes may not be recorded by a study of self-reported mood or ‘happiness.’ But that doesn’t mean that they don’t count!”

Jeanne emphasized that, as a hospice nurse, she has witnessed many people who are near death coming to accept their fate. The ones who suffer the most, she said, are the people still living.

Karoline mentioned that she felt jealous, sometimes, of religious people whom she has witnessed recovering from something as devastating as their own child’s death, based on their belief in an afterlife where they will meet that child again. Dean said he didn’t wish for that flimsy tissue of lies in his life; he didn’t feel jealous of them at all but would rather face facts honestly.

I agreed with Dean… and I wondered if Karoline would really wish that kind of mythology upon herself despite its false comforts. Just to be difficult I gave her an hypothetical… “If I told you that I believed strongly in little dust-men floating at the ceiling of this room,” I asked, “and you could tell that they gave me a great sense of reassurance that everything would be okay (because they were hovering in the form of a triangle! or some such claim), would you really feel jealous of that consolation? Religious convictions are just as absurd as the dust-men, of course — only more familiar and protected by taboos from mockery. So why should their false consolation be any more worthy of your jealousy?”

Karoline clarified that even if she could not conceive believing in dust-men, or any of that supernatural stuff, her point was that it amazed her how comforting such fabrications can be. At least on a temporary basis, they are extremely effective in providing a buffer to the emotional havoc that experience can bring. In other cases, she added, she has witnessed parents without such beliefs unravel completely when faced with the death of a child.

Marie-José had a different story to tell. She explained that in his work her father used to attend the death-beds of many people in their region in Southern France. She has always remembered that he told her once, quite in passing and without further explanation, that the people who took an untimely death the most hard were the nuns in a nearby nunnery. So for these nuns anyway, religion did not provide the consolation it promised — or not enough.

I had witnessed the same, I mentioned, when my grandmother faced death. She had always been very adamant that we would all meet Jesus when we died. (And if we had not accepted Him into our hearts, she had warned, Jesus would shake his head and say, “I don’t know you.” My sister and I used to reenact the telling of this to scare each other.) As my grandmother lay in her hospice bed, however, she showed a great deal of anxiety. Contrast that with my grandfather, who did a few years later. He had never bothered too much with thoughts of an afterlife. Instead he sang fake Puccini arias in fake Italian during his last days.

In the end, faced with these contrasting stories, we concluded that whether you believe in an afterlife or not perhaps plays little role in whether you have anxiety about death… Who knows, maybe there are other factors at play, of which Epicurus and the faithful aren’t even aware?

Walden mentioned, in this respect, that after the sudden death of his mother, he and two of his sisters were able to absorb their loss over time, while the third, who had not been able to reconcile with their mother while she was still alive, still feels anguished by a sense of irresolution.

5. Do We Extend in Both Directions Outside of Our “Brief Crack of Light”?

Looping back to Luis’ comment at the beginning of the meeting, I mentioned that it seemed to me that Epicurus gets it wrong to focus so singularly on this life, this “brief crack of light,” as Nabokov so memorably put it.

Our concerns do extend past our own life. For surely we care deeply about our immediate loved ones even after they die. More than that, we care about our ancestors, our colleagues, our heroes, our friends’ parents, our neighbors. We research our genealogy and our language group. Yet it’s not even restricted to our own personal connections. We care about history. For example, as Yann knows (we have an endless debate going on this), I care deeply about the ideas behind the American experiment in representative democracy, about Lincoln’s understanding of human fallibility as the basis for this experiment (“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right…” or as he meant to say… to the extent that evolution has provided our particular species of bipedal primate with the capacity to see the right…).

Likewise, Yann and Dean and many in our group have already made abundantly clear how much they care about the future, even after they personally will be gone. We care about the effects of climate change, for example, on generations to come. We care about children that we don’t know personally and will never meet.

So our concerns and interests extend into the “eternities of darkness” on either side of us, into the past and the future.

Can we then live a kind of… modified Epicureanism?

Can we adopt Epicurus’ useful outlook in terms of our own lives (letting go of fables, grudgingly accepting that death is final, living simply, recognizing that pain will be manageable), but extend a more active and engaged outlook towards other lives around ours?

To do this, though, we will need a new way of telling stories. For the impact of another person on each of us, in most cases, is based on our living connection to that person. It can be unnerving to realize how little we care about the deaths of people we don’t know, for example. (No doubt that’s why statistics are often said to be “mind-numbing”!) We need something to bridge this gap, to expand the area of our interest.

How many people can we actually get ourselves to care about, looking back and reaching forward?

Once we do care for people, for how many years out can we expect this care to reach?

At what point will our willingness to devote our energies to something beyond our own brief life begin to flag?

In other words, what are the limits to our capacity for love, primates that we are, with brains and bodies adapted for the more narrow purpose of replicating our own DNA?

Does love have limits?

Maybe not?

6. Art and Death

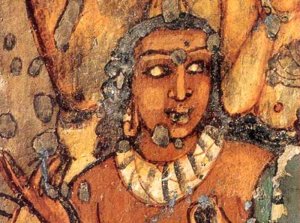

This brought up the final area of discussion. Walden started us off by stating that he has come to the view that art does not need religion, but religion needs art. In other words, without the awe-inspiring Catholic cathedrals with their flying buttresses, without the aching beauty in the cadences of the Muslim morning call to prayer, without the rich colors of the cave paintings of Ajanta, religion would lose its power.

“Yes!” I said. “But that is true for the secularist, materialist, non-supernatural viewpoint as well, isn’t it? We need a new art!

“One that supports a scientific and naturalist angle into love and loss and the whole gamut of experience in between. We need an art that expresses our blissful sense of belonging with other people. We need an art that expresses sorrow and rage and confusion in the face of suffering, so that even people we don’t know can be seen as more than a statistic.”

I noticed Renée looking at me sideways, as if to say, “What are you on about now, honey?” But I kept going…

“As it is, art is experienced, more often than not, as separate from meaning, in a realm of its own. Sure it can stun us with beauty, or shock us, or make us wistful, but it usually doesn’t inspire us to action. We don’t expect it too either.

“That’s fine. I am all for art for art’s sake too. I distrust propaganda or heavy-handed meaning in art as much as anybody. But maybe, just maybe, in this context of asking ourselves how to live, art can do more?”

At this, Claudine shouted out: “Why do we need a new art, Tom? When I see time-lapse photos showing the melting of ice in the Arctic, I feel ready to take action. When I see a documentary on polar bears leaving their hunting grounds, I don’t need more than that. What do we need art to do in addition to that?”

“Well, you may be unusual, Claudine,” I answered, “I think most people need more than photographic documentation, more than the blunt facts of the matter. They need engagement. Again, not propaganda, but at least a direct acknowledgement that love is at the core of the work, as well as pain. That we aspire to preserve good things, gentle things, kindnesses, ambiguity, gratitude. It seems to me that most secular art does support these values, but it does so almost haphazardly. Is there a place where it could be done more intentionally, just as traditional religious art has done, for the purpose of increasing understanding, growing love, reducing suffering?”

Heléne emphasized that it all comes down to storytelling. As a marketing executive, she explained that she knows this is always the key to conveying information. (But is it only better marketing we are talking about? That struck me as depressing. Isn’t there more at stake here? An aspiration to love one another in a more lasting way? Isn’t that beyond a marketing plan, even while it demands it?)

Walden said that although he didn’t want to be cynical, he didn’t believe any art could make a difference in people’s actions on issues such as climate change. He expects us to continue emitting carbon into the atmosphere, until the younger generations end up taking to the streets in mass protest. No art could change that. Dean agreed and spoke of how ephemeral our emotional states are, our feelings of empathy most of all. They won’t last, he insisted.

“But certainly it’s worth a try!” I said.

Someone asked provocatively: “What good can a painting do, Tom? What has art ever done?”

I stood and hung my arms out to the sides. “Are you kidding me? When people walk through the Uffizi Gallery and gaze at paintings of Christ being crucified, I think when the painting works they look right through the dogma of religion. They see a human being suffering unjustly. They see his mother and friends in agony, helpless, as they look on. These images stay with them, lodge in their hearts, one might say despite the religious indoctrination that limits and squelches their meaning. Art can change the world. Has. Over and over.”

Renée mentioned that while hearing a countertenor sing a Bach Cantata last Sunday at a concert in Berkeley, she felt changed in a way that is lasting. Or staring at Monet’s haystacks a few years ago at the Metropolitan Museum.

Sometimes you can’t put it into words, but you are expanded in a way that you hadn’t been before the experience, and it alters how you act in the world.

7. Winding Up

It was getting late so we had to end. I realize, writing this, that in two meetings we have already set a high bar for what we do!

In our first meeting, we came to the realization that we need a new origin story, to supplant those of religion, one that accords with the latest science of primatology, anthropology, neuropsychology and prehistorical archeology.

Oh, and in the second meeting we realized that we needed a new art that allows us to reach into the two “eternities of darkness” — i.e. reach into the past and the future — surrounding our brief lives. We need to live with Epicurean simplicity and modesty, yet, nevertheless, with the assistance of art, learn to dream, grandly and ambitiously, outside of the narrow experience-frame of our own lifespan.

Alrighty then!

Got our work cut out for us.

See you all next month when we meet on the Winter Solstice. More on that to come.

As always, if you remember something from the meeting that I overlooked (and there are surely many things) please add it in the comments!