SUNDAY OCTOBER 18, 2014

The first meeting! It begins.

When we had all taken our seats in the living room, shortly after 8:30 pm, I started us off by sharing my thinking behind the name of our group.

1. Why “the Old New Way”?

We are doing something new tonight, I said.

But we are also doing something very, very old. We are asking the same questions that have been asked by, well… by pretty much everyone, all through human history.

Who am I?

Why am I here?

How should I act?

What happens after I die?

And as we will see (in our readings going forward), even taking a strictly non-supernatural approach to these questions is not new.

Hence the “old” part.

But then, you might ask: how are we are doing anything new at all?

For one, this is new because… we are doing it here and now, in October of 2014. The mere fact of our timing, in this place, at this moment, makes it new.

For another, this is new because… we have no idea where these meetings will lead us and how we will grow from them.

More than these points, however… there is another important way that I think what we are doing is new:

We will have to fashion a new language even to talk about it.

2. Why Will We Need a New Language?

I elaborated a little more on this point:

The languages and associations we all bring with us to this first meeting, I suggested, are steeped in old dichotomies, old categories, old habits. No fault of our own; that’s just how it goes.

For example, unless we deliberately resist it…

- we tend to think that rationality operates independently from emotion;

- we tend to think of capital “M” Meaning as being “out there,” separate from an individual’s assessment of it. (We are in the habit of craving “objectivity” in all aspects of our lives);

- we think of there being at least the possibility of reconciling all of our values and aspirations in a unified way, if only we could… just get it right;

- many of us seek unseen realities, which are sometimes characterized as “transcendent” realms;

- we think of “the animal part” of each of us (in so far as we acknowledge it at all) as a wild, impulsive nature, which must be directed into the proper channels (by what? The “non-animal part” of us?).

Much of this is a product of millennia upon millennia of religious, or so-called “spiritual” thinking.

This type of talk has infiltrated American’s politics especially, since our “rights”-based revolution drew from French Enlightenment thinkers, worshipers at the altar of Reason, as well as Platonic/Judeo-Christian traditions of thought.

It is the air we breathe.

We will attempting to refashion language in this group. Sounds ambitious, doesn’t it? And it is! I want us to actively contest these usual categories…

- changing our orientation of ourselves so that we do not forget our status as evolutionary beings, animals formed by cross-currents of adaptation, not perfectible or pure in any sense but rife with contradictions all the way down;

- reminding us that we are animals in everything we do (yes, even when listening to Mozart while doing higher math– all the way down);

- looking with fresh eyes at our contemporary notions of “love,” “death,” “work,” “good,” “evil,” “real,” and so on; and

- making sure to pay attention to our wordless, emotional, strangest responses, as much as we pay attention to what can be more easily articulated and affirmed by others.

I think we should embrace the confusion that this will cause us.

Confusion will be our friend in this process, since it will signal when we are getting somewhere.

3. Some Very General Guidelines for Our Group as We Begin

At this point, since this was our first meeting, I shared with the group some very general guidelines that I thought would be worth mentioning.

First, I said, I want to encourage complete freedom of expression in this group (and all the time! Why not?).

I don’t want there to be any confusion on this point… What I mean is that ANYBODY is encouraged to say ANYTHING and EVERYTHING at ANYTIME.

(As those of you who know me have already witnessed, I sometimes try to pursue a thought by saying provocative things, or extending the logic behind an argument to its limit… And I want you all to feel free to do that too!)

We all know, of course, that words can never adequately express much of what we will be exploring in this group. But – hey, we have words, and we should not be afraid of them just because they are inadequate.

Second, this group will be focused on finding non-supernatural ways of looking at the world and our identities in it.

This means some approaches, although they surely can be expressed, may not be where we stay.

Other groups (“places of worship,” as they are called, certain spiritual retreats, and so on) often use the language of “faith” and “transcendence” and “God is love” and the like. That probably won’t be the case here — where we will be more inclined to leave God out of it entirely and just go with the love.

I am interested in keeping our focus on thoroughly natural concerns and experiences. This life. This world.

It is my hope that these parameters will give our group its unique interest — and its value.

Third, it’s okay for us not to agree.

I want to say from the beginning that I expect everyone here to have a very idiosyncratic experience with this group.

For some this group may inspire you, for others it may frustrate you. Some of us will perhaps be changed by it, perhaps for the better; others of us may feel blocked, or made anxious, or even angry at times.

That’s fine.

It would be wonderful if we all arrived together at a rich synthesis of emotional awareness and philosophical understanding by the end of our meetings. But then again, it would be disturbing too if that happened – wouldn’t it?

And anyway, I asked the group, don’t you find that, with surprising frequency, the very things you were most certain of ten years ago are the things that you feel completely different about today?

Let’s cherish our disagreements.

4. A Breathing Exercise to Begin

To start us off, I asked those present if I could lead us in a very brief… breathing exercise, before we plunged into our discussions. (I explained that I have found from experience that I think more clearly — and more intuitively — when I do this.)

So with only a slight feeling of awkwardness, and lots of good will, we closed our eyes and steadied ourselves for a moment before beginning.

5. The Question of “Attentiveness”

Not wanting to take any more time, I started us off at this point with a simple query for the group…

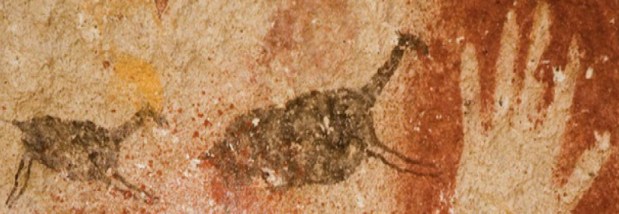

When we think of prehistoric people, I said, we imagine that they were extremely attentive to their surrounding — a leaf rustling, a change in the weather, a crooked branch that might be used as a tool.

But in thinking of them in this way over the last weeks it struck me… that we don’t want to over-romanticize them.

So my question was: Are we just as attentive now as prehistoric people were — only to different things?

Marie-José answered quickly and decisively, as those of us who know her would expect.

“Yes we are equally attentive!” she said. “But the stakes are much lower for us. We pay attention to which loaf of bread we want to buy at the bakery, or how to access an email on our iPhone while talking, or what music we want playing in the background as we drive. But for prehistoric people, a wrong decision about the weather, or what to listen to, could cost their lives. That is the difference!”

Lucie argued that we may be attentive, as Marie-José suggests, but in a far more superficial way. We don’t take the time to experience the fullness of what we are doing. Richard agreed that the distractions and busyness of our lives are such that we tend to glance from thing to thing. And it is getting worse, he suggested, in the digital age. “We are constantly being entertained,” he remarked.

Renée spoke of her recent experience of watching two men walk together down the sidewalk in San Francisco, both listening to music through bulky headphones. She couldn’t but help think how sadly unaware they seemed of their surroundings — and each other.

Sylvaine commented that she thought an important difference is that prehistoric people had more space.

Setenay questioned the vagueness of the term “attentive.” She wondered if we may be as attentive as prehistoric people, but not as “focused.”

Dean raised a contrary view to the one expressed so far.

He explained that he guessed we actually ARE as attentive, since our cognitive abilities are probably quite similar to prehistoric human beings. After all, the stakes for us when driving are certainly high. The stakes of which medication to take for a disease can be as high too. And many of the social and career choices we make have very serious consequences for us.

For Dean, then, we are simply in a different context, and we have adjusted accordingly.

6. Seeing the Whole Animal

I spoke up at this point to say that, although I agree generally with Dean that we are probably similarly attentive to our surroundings — though very different in what we choose to focus on — there is one aspect of our attention that seems to me markedly different.

Namely, we usually view animals as separate from us, inferior to us, almost as objects “That damn raccoon got into the garbage again last night!” I may mutter, never thinking of the raccoon as anything but a nuisance.

Whereas, as the reading brought out, prehistoric people likely saw animals as equally whole and present beings. We might speculate that a prehistoric man would have said something like… “Oh! That raccoon with the slight bend in her tail, you know the one we saw two full moons ago, she was hungry and found our meat scraps to feed her children. I wonder if she is ill?” (Not to say my prehistoric counterpart wouldn’t then throw a rock; I’m not imputing more generosity in this case, just more awareness.)

Cave paintings from the prehistoric era often depict a nuanced, shadowed, fully rendered animal, and then… a human stick figure. George Bataille (in one of our readings) speculates that this is because human beings, for most of human existence, did not perceive of themselves as the protagonists standing above and apart from their prey. They knew many animals around them to be graceful, fast, powerful, wily. They readily observed these animals undergoing their own mental and emotional processes. Surely, they were worthy of being rendered in detail.

Humans, on the contrary, are often a minimal element: the one holding the spear, the one hunting, but hardly the focus.

I drew the group’s attention to the illustrations in a book entitled “The Dawn of Man,” which I have had since a young boy. One in particular cracked me up when I pulled this book down from the shelf last week in anticipation for this meeting.

It depicts a distant relation of ours, Heidelberg man, from the Middle Pleistocene of Germany.

What amuses me about this artist’s rendering is that this primate relative is posed in a manner suggesting the Mona Lisa, staring at us in the foreground, with a line of lush trees creating depth of field behind. We can imagine that this would never have been the way that prehistoric people would have rendered themselves. It assumes an entire ideology of dominance over, and separateness from, nature, in its very composition.

Here it is. See?

Something about the modern assumptions behind his “pose” just gets to me every time I look at it.

We talked more about our relationships to animals. Renée embarrassed me by describing the elaborate growling noises and the bizarre contortions of my body that occur when I try to chase off a neighborhood cat who is terrorizing our own. I conceded that this is perhaps the closest I get to a communion with an animal, since I have to imaginatively enter the mind of a cat defending its territory to embody it.

Richard pointed out that if, in prehistoric times or any time, humans perceived themselves as “equal” with other animals, than rather than suggesting their equality, this very perception marks them as strikingly different! No other animal, he conjectured, would try to see deep into the eyes of a human so to experience its wholeness. It would simply see delicious flesh to tear with its teeth. Or a clumsy, crashing figure, smelling of fear, tufted with hair, from which to flee.

So the cave drawings of prehistoric humans might actually suggest the uniqueness of human consciousness, leading through our symbolic thinking to a kind of imagined meeting-of-the-minds with other animals (where, in fact, one can never occur).

This point led me to read aloud to the group a poem by Robinson Jeffers, which takes Richard’s point about the absurd and self-denying nature of this impulse to see ourselves as equals to other animals to its logical conclusion:

Vulture

I had walked since dawn and lay down to rest on a bare hillside

Above the ocean. I saw through half-shut eyelids a vulture wheeling high up in heaven,

And presently it passed again, but lower and nearer, its orbit narrowing. I understood then

That I was under inspection. I lay death-still and heard the flight-feathers

Whistle above me and make their circle come nearer.

I could see the naked red head between the great wings

Bear downward staring. I said, “My dear bird, we are wasting time here.

These old bones will still work; they are not for you.” But how beautiful he looked, gliding down

On those great sails; how beautiful he looked, veering away in the sea-light over the precipice. I tell you solemnly

That I was sorry to have disappointed him. To be eaten by that beak and become part of him, to share those wings and those eyes–

What a sublime end of one’s body, what an enskyment; what a life after death.

7. Humans — Understood as Animals — Dealing with… Climate Change?

Dean spoke up to say that he is convinced, and has been as long as he can remember, that we are merely animals. That’s no problem for him to accept.

It troubles him when he thinks how humanity’s self-aggrandizement, over the past 5000 years, has led to terrible consequences by severing us from nature. This is what we do, he insisted, as animals who think they are “special”: consume resources at a high burn rate, putting the planet at risk.

Now, though, Dean argued, we must use our developed prefrontal cortex, our ability to reason, to reverse the damage we have already done. The only way to tackle climate change, for example, is to… get over our short-term thinking and self-defeating behavior brought on by our genetic predisposition.

I pointed out that there is a tension in Dean’s outlook. On the one hand, he seemed to be saying that we need to accept our status as animals, so we don’t sever our connection to nature. On the other hand, we need to “rise above” it to save the planet.

I questioned whether we really “rise above” our animal nature. Again, this seems to me a language of the past. Our prefrontal cortex, and our ability to represent our world and thoughts in symbols and verbal language, are, in fact, also part of our animal nature, are they not?

I drew on the analogy of a camera — with an automatic setting and a manual setting. Most of the time we operate on the automatic setting in our brains. This leads to some good results (“common sense,” it is often called). But in an increasingly complex world, it leads to some terrible results, very out-of-focus pictures, too. For example, one thing that is part of our “common sense” is that we tend to be suspicious of people that look different than us (automatic setting). As the world becomes more pluralistic and diverse, this hampers trust and open communication (in addition to being hurtful and unjust). So we become educated and learn to use our “manual setting” to make sure that we do not judge people harshly because of perceived differences (when you think about it, our legal system at its best is a kind of enforced manual setting — innocent until proven guilty, rules of admitting evidence, etc.). But my point is, I continued, it is important to recognize that BOTH of these systems belong to our animal nature. To “rise above” perpetrates the same separateness that Dean rightly condemns.

He conceded this. But his point still remained: how do we, animals that we are, deal with a problem like climate change?

Penda commented that, in her experience, the more simply people live, closer to the land, the more responsible they are about not damaging their environment. So by living in a small setting, among people whom one considers whole and irreducible and unique, among animals that one knows and respects in all of their wholeness too, people become more attune to living harmoniously with nature.

Yet Lucie pointed out that when we are in this present state we often cannot see the long-term, abstract consequences of our actions. Climate change, after all, would not be detected by people living simply in a small village. They would detect famine and drought (the effects of climate change), but they would not see the centuries long trend lines.

The combination of these two points struck me as a tremendous insight, which we may need to grapple with many times in this group.

We have two very different capacities as humans. On the one hand, we have our ability to live simply, attentively, and rewardingly, in a small community. I think of my mother’s extraordinary ability to be loving and present to everyone with whom she meets during her day. I think of the generosity and hospitality towards strangers often demonstrated by people living in rural settings the world over. On the other, we have the capacity to abstract from our experience, to see people as data points, and create models of our world. The remarkable edifice of science is a result of this approach — we learned to look to impersonal data, to rely on objective standards (interestingly, the values of science are, contrary to how our culture depicts them, very personal and human-centered, I would argue — truth-telling, evidence, parsimony, verifiability. But that is an argument for another time.)

The problem is that as we turn away from the more personal to our more linear or abstract thinking, our “prefrontal cortex” thinking if you will, we become ever more removed from that small village sensibility, that subjective and emotional connection to the world around us…

Perhaps, I asked, there may be a way to bridge this gap?

Perhaps there will be a way to use our “small village” sensibility to create, metaphorically at least, a link to the abstract knowledge that comes from leaving it behind? This, I would contend, is the only hope we have for combatting climate change.

Not dry argument, but personal, emotional –even, shall we say, tender? — engagement on a global scale. Is that even possible?

Otherwise, as a few of us had joked earlier in the evening, someone can feel very alarmed about climate change and carbon levels in the atmosphere — until he or she is offered the keys to a shiny new, leather-upholstered SUV for free — Look! It’s yours and outside the door now! At this point his or her neural networks light up brighter, I am afraid, in the desire centers of the brain than the low-level glow in his or her neural networks brought on by thoughts of climate change. We all fail this test everyday. It will have to be personal.

Again, being animals, I argued, I don’t think it coherent to think of us overcoming or “rising above” our nature. We must engage it, acknowledge it, and see the earth in a new “whole” manner, as a once stranger who is now our guest…

8. A Discussion About One of the Readings and Our Approach to Knowledge

A few members of our group, Marie-José, Setenay and Miriam, raised their objection to one of the reading selections for this month.

They were okay with the discussions of the practices of native peoples of America in The Ohlone Way and The Way We Lived. Nobody spoke to Abram’s Becoming Animal. And although Florence complained about the awkward translations, the poems largely passed muster too.

But the two chapters that I excerpted from The Cradle of Humanity by George Bataille really irritated some members.

Marie-José felt that Bataille’s tone was typical “white male”: impossibly certain, patronizing, self-involved. Setenay called him “unbearable.” Miriam shook her head in dismay.

Others in the group acknowledged that his tone was a little dated — we laughed about how he mentions his feud with Sartre at the beginning of one lecture with not a little self-inflation. Yet many of us did not find it so off-putting; you might say we discounted the “white male” obtuseness and read him for what insights he might have despite his dated tone.

After all, I argued, Batialle does acknowledge that he is not himself a “pre-historian,” and he concedes that his speculations about prehistoric cave paintings and culture are just that — speculative — right? He is admittedly just making it up as he goes. So, I asked Marie-José, is it that you don’t think he should be making these kind of speculations or assumptions at all? Or that he simply makes ones different from the ones you make?

Setenay clarified that it was not just his tone that troubled her. She said he was indicative of a larger confusion that she had with our group: she found herself torn between the two very different approaches we seemed to be taking towards understanding prehistoric people and their world.

On the one hand, when she learned that this was to be the topic, her expectation was that we would review the latest scholarly literature in the fields of paleoanthropology, paleoarcheology, etc. Then, she figured, we would be very specific about what claims we are making in terms of burial sites, tools, etc. That, clearly, was not the approach we took.

Or, she realized, we might look at prehistory as a metaphor, knowing that we are not necessarily getting an accurate picture of their lives, but using our imaginations to conjure a world that we can stand up as a kind of mirror to our own. This, she discovered in the readings and in the meeting, was more our approach.

Yet she found that Bataille’s looseness made her long for a more academic approach. Being a scientist, she wanted to get more specific in our data.

I thought this was an excellent description of two general approaches we might have taken. I explained that, although a more scholarly approach would be, without a doubt, fascinating and worthy, that doesn’t strike me as within the purview of this group.

At UC Berkeley there are no doubt in-depth courses meeting this fall that examine the prehistoric era. (Although even these scholars get it wrong and face ongoing disputes in the field, we can be sure that they are admirably getting closer and closer, with careful scholarship.)

I explained that my idea for this group is different, however. It want to use our readings each month as a kind of metaphor, a kind of mirror held up to our own present-day lives.

Any tension she felt on this I agreed is certainly valid, however — I feel it too. And I think it is a tension that we will feel often, as we read excerpts (but only excerpts, for lack of time) from different philosophers and poets and artists and writers and scholars and scientists from different historical epochs, with the aim of provoking us… instead of getting the scholarship exactly right.

(E.g. David Hume’s drawn-out epistemological argument about “secondary qualities” is not going to get as much time in that month’s discussion as his explanation of how human beings develop moral principles by way of a public language of praise and blame. Sorry, but we have to prioritize…)

To the argument that our approach might be miss certain things that a scholar would consider important, therefore, I would answer: yes, undoubtedly! But if we are seeking a rewarding and possibly life-changing alteration of our sense of ourselves as we live today, then sticking with a straightforward academic approach would, I would argue, also potentially miss important things.

For sometimes the scholar can miss the forest for the trees; in such cases he or she may only indirectly touch on the great forces working under the surface in our lives: our sense of ecstasy, of love, of sorrow, our fear of death, our deepest commitments.

And anyway, metaphors, we should remember, are not lightweight — they are a way into ourselves. They are, ultimately, how we frame the narratives of our lives. I would argue that both the academic approach and the more reflective approach are worthy.

9. Looking to Prehistory for an Updated Story of Our Origins

Setenay and I had a chance to carry on our discussion after the meeting, and by the end of it I believe that we arrived at a clearer picture of why looking at prehistory is useful.

It struck me, talking to Setenay, that even while pursuing a strictly non-supernatural approach to the important questions in our lives we still feel a need for a compelling story of our origins — if only as a kind of starting-point to our investigations.

These origin myths have important consequences.

Think of Hobbes: the “life of man” in a state of nature is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.”

Think of Rousseau: “Man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains.”

Both are myths of what we were like in a “state of nature,” leading to very different conclusions about how to organize society.

Now here’s our chance… What do we want to base the story of our origins on?

The latest scholarship?

A piece of fiction we make up, whole-cloth, in the vein of Hobbes and Rousseau (or Christianity or Hinduism or other religions)?

Or something in between?

We would hope that our updated story will not fall prey to the magical thinking and creaky in-group/out-group thinking of the old Bronze and Iron age myths of the major religions. (Enough with the snakes and the booming voice of God, please.) Yet we can admit that, no matter how hard we try to resist it, we will ultimately have to base even this updated story of our origins on finite knowledge. Revision will always be necessary.

Again, this is not to say that an updated story of our origins will be equivalent to all other myths, from Christianity to Islam to Wicca to Ayn Rand’s Objectivism… Some myths are outdated and based on obviously dangerous or damaging beliefs. Let’s not fall into the trap of false equivalence!

But, yes, just as science is always indeterminate and ongoing, our understanding of the world around us and our own selves will always be indeterminate and ongoing.

I concluded from this conversation that we certainly do not want to make it up whole-cloth. After all, we are hoping, with all of our limitations, to develop an understanding of ourselves that resonates with our current knowledge about the world as is. And this requires adherence to the facts as best we know them. Then we can take it from there…

So I ended up, after the meeting, feeling more conscious than before of the need to explore our “story of origins” based on the latest paleoanthropology, paleohistory, paleoarcheology. Even knowing that we are looking at it as a metaphor, we will benefit from being as accurate as possible.

In short, I think we should revisit this in another meeting! Thank you Setenay!

10. One Last Round

Brad got our attention, near the end of the meeting, as it neared 10:30 pm, by bravely stating that the evening’s discussion had left him feeling “disturbed.”

If we are only primates — animals — he explained, then he found himself feeling horrified at the prospect that he is part of this species. Considering the damage we are doing to the earth, considering the crass culture around us, then he is finds himself implicated by this particular bipedal primate species’ failings.

I roared back (he’s my best friend, so I can do that with Brad):

“Disturbed? Why is it disturbing? For all of its vulgarity and violence, the world is full of extraordinary beauty too! Just look out that window,” I said, pointing out to San Francisco. “Think of the wonders out there. The medicines that save lives. The gas which gives us a warm fireplace right now. Look at the faces in this room, how full of love and longing each is…”

“I’m disturbed. I don’t want to debate you, Tom. I am saying how I feel.”

“And I love that!” I exclaimed. “I am glad you did. But I am giving the opposite perspective. I think if we accept ourselves as animals then it is clarifying — and liberating. Finally, we can look honestly at the choices we make, the trade-offs, the responsibilities we want to take on or choose not to take on…”

Nadine spoke up to say that she felt that humans, animals that we are, have a sense of guilt and shame for what is done by our species. We are aware, she said, of the many bad people in the world, the ones doing damage or inflicting cruelty, and it makes us feel implicated. Walden supported this by observing that we are the only animal who feels remorse.

But I challenged this too (holding back the roar this time): “I think this is a case where the language you are using is archaic,” I said. “There are not “bad” and “good” people. We are ALL implicated because we are ALL capable of making poor choices, complicated choices, and all of our choices do harm to someone, deprive someone of resources, exclude someone. Think of private property — right now there are people hungry, in Berkeley, and a monopoly of violence that we assign to the State prevents them from eating because of an artificial construct called ‘property’!

“Which brings us to the value of accepting our status as animals again,” I concluded. “Once we accept that there is no escape from the hodgepodge of impulses and motivations and last stands and sudden reversals that is our brain, then — only then — can we start to talk honestly about how we want the world to look. And what we are willing to do to make it look that way…”

It was a debate that surely we will continue.

Great meeting, everybody. Much to think about. I am so thankful for the open-hearted and open-minded way everybody at the meeting participated.

As always, please make any additions or corrections you have in the comments below.

See you next time!